In Memoriam: Gene Zema

Innovative Northwest Architect

Born on September 2, 1926, Gene grew up on a farm in California in the Sacramento Valley. He came to the University of Washington as an engineering student in 1944. He then served in the Navy during World War II, and upon returning to the University of Washington, changed programs and joined the Department of Architecture. He graduated from UW in 1950 with his Bachelor of Architecture degree.

SEATTLEITE, ARTIST, AND ARCHITECT

Gene was a man of many talents and interests. While at the UW, he held down three jobs to afford the college experience and was a part of the swim team that in 1945, completed a nearly perfect season.

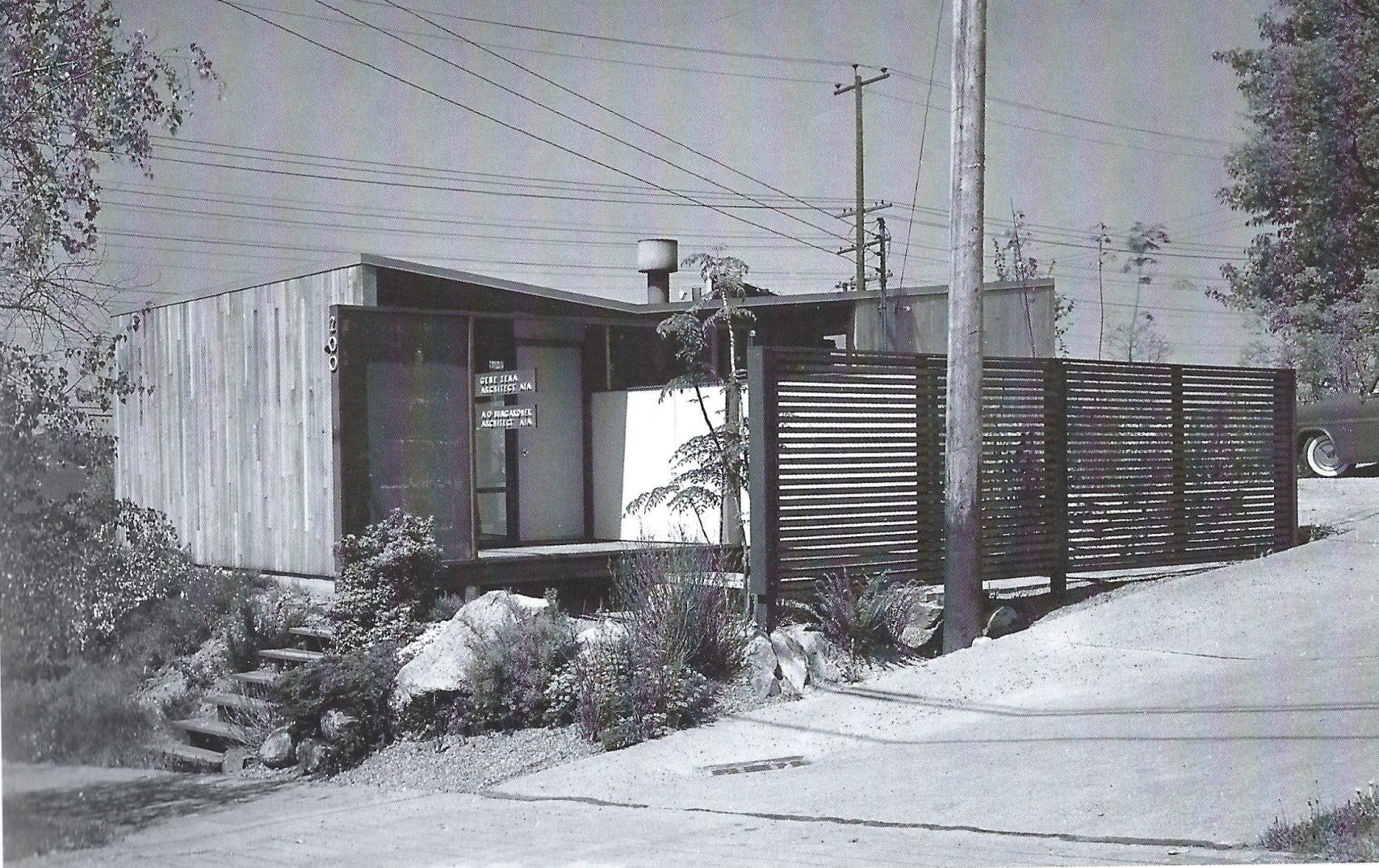

Gene received his architectural license in 1951. He joined the American Institute of Architects (AIA) that same year, and was the first of his class to do so. Opening his own firm in 1953, he built a small office on Boston Street off Eastlake Ave in Seattle and began on a house of his own design for his growing family. Janet and Gene welcomed their first son in October 1952 and their second son a year later in November of 1953.

The house in Sheridan Heights, in the north Seattle area, was a departure from some of his early work, with a rectangular build and gabled roof, complemented by large windows and ample decks to enjoy the surrounding views. This house won the AIA Home of the Month and was awarded the very first Home of the Year award in 1954, and in this same house, Gene and Janet welcomed their daughter, Jane, that same year.

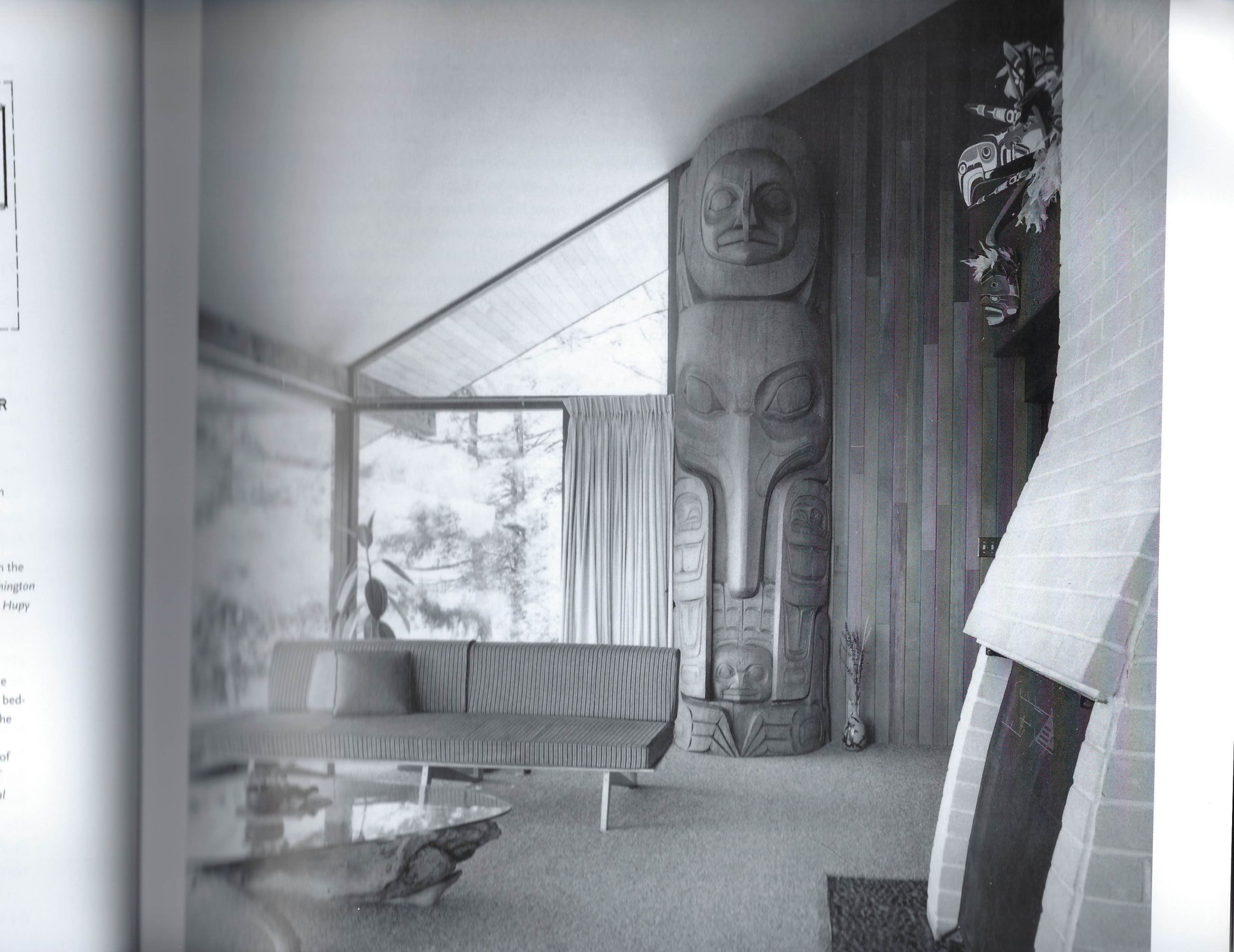

Gene had increasingly become interested in regional indigenous art from the Pacific Northwest; he collected many Northwest coastal indigenous baskets and created large murals with Kwakiutl motifs. This interest was one he would pursue the rest of his life, incorporating many of these elements into his projects. In fact, Zema incorporated much of the Seattle area and Pacific Northwest into all aspects of his designs and builds, a monument to the area, history, and people of the region.

In 1960, Gene expanded the Zema office spaces, designing and building a retaining wall using cobbles salvaged from the I-5 Freeway redevelopment project. The Zema office building, with its “intimate scale and quiet richness,” according to UW College of Built Environments Department of Architecture Professor Grant Hildebrand, has long made this building a local landmark. The Zema Office building still stands in the Eastlake neighborhood and is emblematic of Gene’s architectural style and skill.

NORTHWEST MODERNISM

Utilizing natural Northwest materials, particularly wood, Japanese-influenced designs and dramatic, geometric interiors highlight Gene’s aesthetic taste. This style, combining midcentury modern design within the local architectural and landscape context, became known as the Northwest school. It was developed and practiced by Zema and his peers, including Paul Hayden Kirk, Ralph Anderson, Fred Bassetti, Al Bumgardner, Daniel Streissguth, Roland Terry, and others*.

These natural elements and open, dramatic floor plans, typified The Northwest School movement, which lasted through the 1950s and 1960s. A typical element of Gene’s personal style was to integrate the Northwest wooded surroundings and natural landscaping into this work on the build. This method allowed the natural ecosystem to thrive.

“He was all about aesthetics,” Jane Zema Summerfelt says. “He didn’t seek approval of others in his style and he showed little regard for current trends. He built what pleased him and that pleased his clients; he built what he liked.”

Gene’s style combined with the natural elements found in the Pacific Northwest did not lend itself to skyscrapers and high rises. Rather, the neighborhoods throughout Seattle are punctuated by local clinics, neighborhood churches, branch libraries, and houses with these natural elements and generally high-pitched roofs, all signatures of Gene’s work.

“Windows were generous in their expanse to claim the striking views of water and mountains.” – Grant Hildebrand

With the Northwest school movement in full swing during the 50’s and 60’s, the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) provided universities and colleges with grants to acquire small nuclear reactors for research programs. The University of Washington was one of those programs, offering nuclear engineering classes as part of the College of Engineering in 1953 and forming a Department of Nuclear Engineering in 1956. In 1957, the AEC approved funding to build a nuclear reactor building on the UW campus to house research, office space, and classrooms.

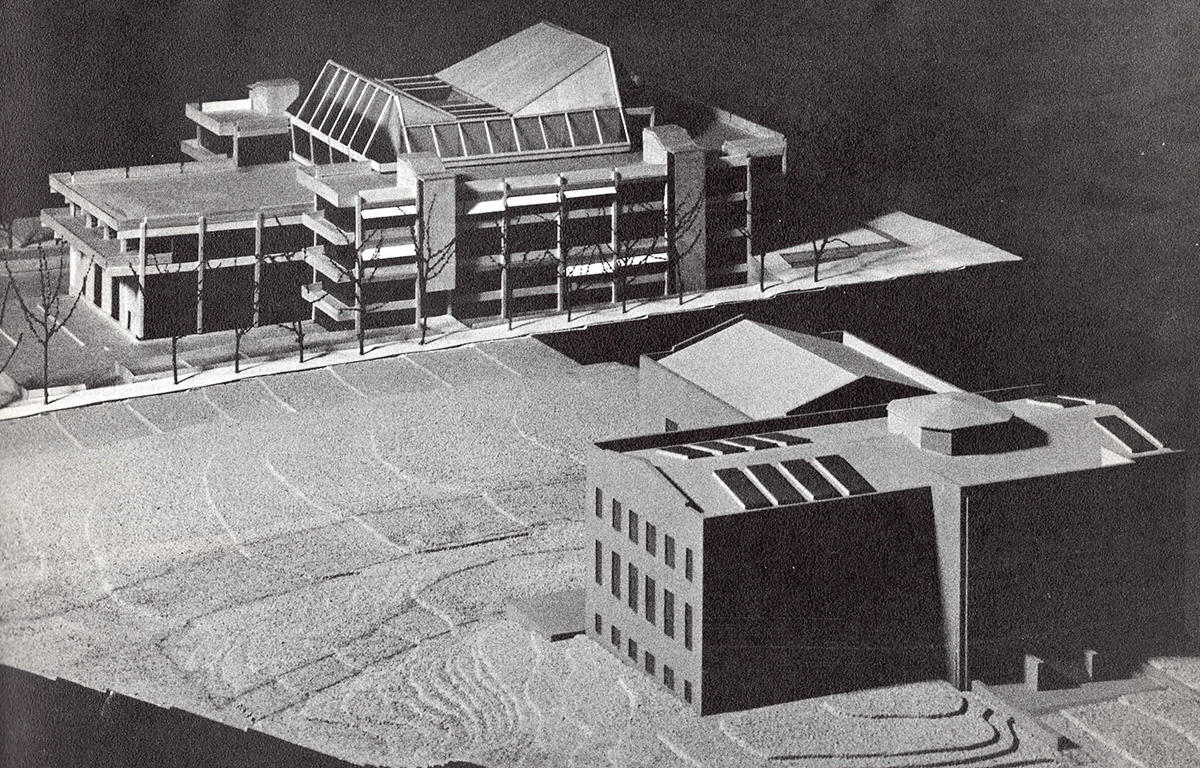

Members of the UW faculty in architecture joined forces as The Architect Artist Group, known as “TAAG,” and in a unique collaboration with the engineering department, designed the Moore Hall Annex building. TAAG architects consisted of former schoolmates Gene Zema and Daniel Streissguth, and Wendall Lovett, all members of the UW Architecture faculty, as well as artist Spenser Moseley. This group of architects and designers conceived of the one-of-a-kind structure as a concrete box with large windows, allowed the public to witness the modern alchemy and engineering that took place within. Completed in 1961, the building highlighted UW as one of the first public institutions to get a “teaching reactor.”

Making the nuclear research transparent to the public was a key point in building the brutalist Moore Hall Annex building. The design was a departure from Gene’s signature style of natural elements and more geometric angles. Though the reactor was decommissioned in 1988, the Moore Hall Annex remained a focal point of collaboration and brutalism on the UW Campus until 2016.

However, this was not the last time Gene and Dan would partner as friends, alumni, and UW Architecture faculty. In fact, their next collaboration with UW would produce the building that still houses the College of Built Environments today — Gould Hall.

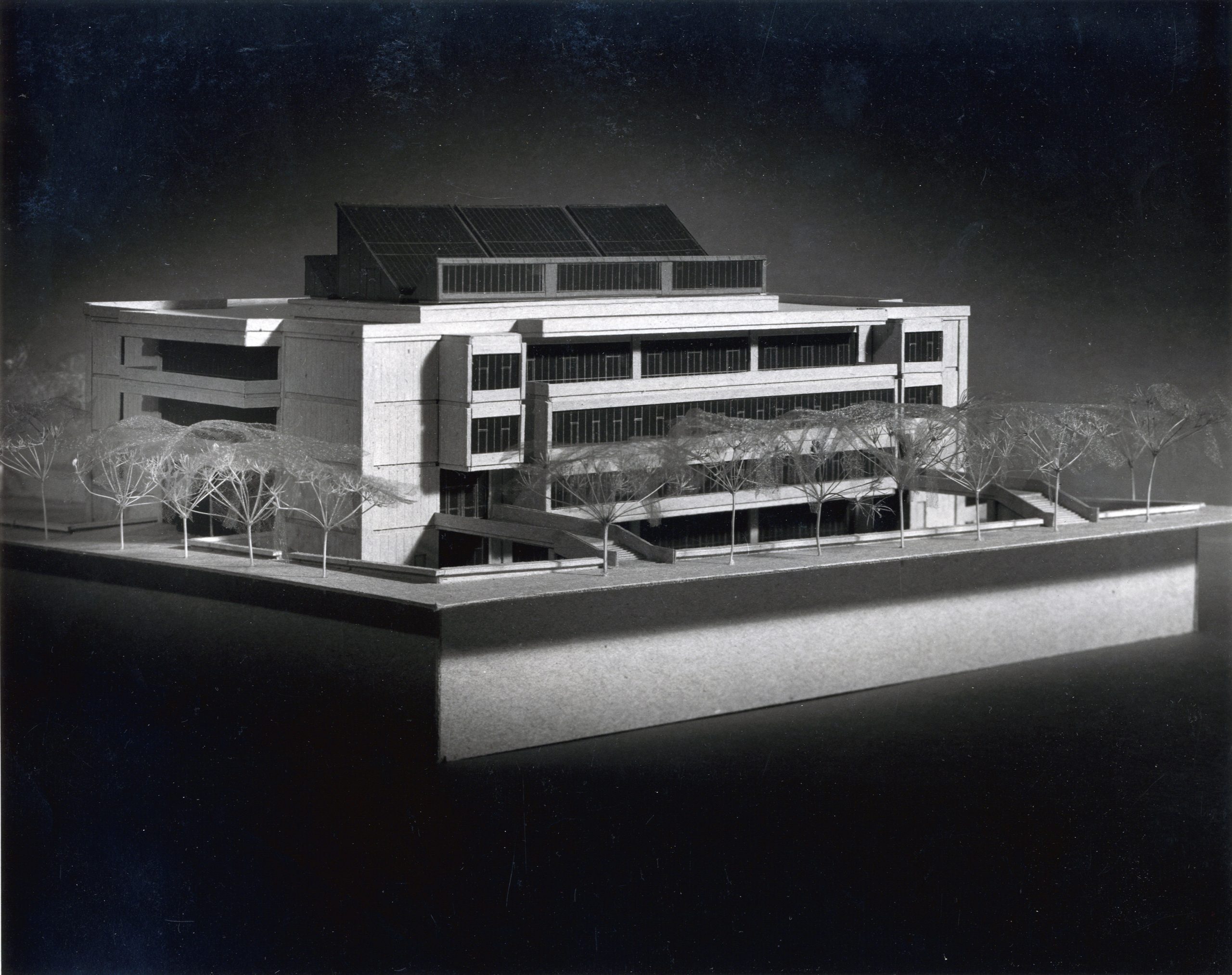

BUILDING GOULD

In the mid-’60s during the height of the Northwest School’s influence, Gene Zema and Dan Streissguth embarked on a new project together. In 1966, Dan Streissguth was selected as the architect of a new building for the College of Architecture and Urban Planning. At this time, Streissguth was the chair of the Department of Architecture and asked Gene to not only participate as a full partner, but to house the project in the Zema Eastlake offices.

The brief for the new UW building directed the team to create a “useful, well-balanced” structure to include offices, classrooms, studios spaces, a library, and space for the design disciplines to collaborate. Gould Hall is a significant achievement because it greatly expanded opportunities for architectural education beyond Architecture Hall, and gave the College of Architecture and Urban Planning its first purpose-built educational space.

The University of Washington Department of Architecture Centennial Celebration brought together the original architects of Gould Hall (1967-71) — Dan Streissguth, Gene Zema, and Grant Hildebrand — with Gould Pavilion (2014-15) architect David Miller, among others.

BEYOND THE BUILDINGS

Over his 30+ year career, Gene won more than a dozen regional AIA awards for his work. Those included the Holm residence in Richmond Beach (built 1956, AIA honor award 1962), and the Lupton residence (1961) on Mercer Island, which was awarded both a Home of the Year award in 1961 and an Honor Award in 1962.

Gene stepped away from full-time architectural practice in 1976, but continued to be heavily involved in building and design throughout the region. He also continued to pursue his outside interests, including collecting indigenous and Japanese art, designing and building homes for special clients, and preservation of the Pacific Northwest. He made more than 50 buying trips to Japan for his shop: Japanese Antiquities Gallery, on Eastlake.

In 1983, at the age of 57, Gene and his wife Janet bought land on Whidbey Island with the intention of establishing part of the land as a nature preserve. This 70-acre plot included wetland and meadow within the Ebey’s Landing National Historic Reserve. Here, Gene began designing his new home. It was truly a family project: Jane Zema Summerfelt recalls gathering the field rocks for the shower stalls and fireplace with her children. Her husband, Todd, and brother, Gary, spent many a weekend with a hammer in hand as the compound was built. As she had throughout her life, his wife, Janet – also a UW alumna – supported and celebrated the project with memorable meals and gatherings of many friends.

The house on Whidbey was completed in approximately 8 years and was a particularly personal project for Gene. In the Seattle Times in 2007, Gene said about the Whidbey Island house,

I wanted to see if I could do this myself, from the ground up. It was satisfying. I think architects should do that. I think it should be required. There’s a tendency now to be more concerned with how the house looks from the outside than with how it works. The sculptural idea. I think architects ought to take a course in clay and get some of that out of their system. Fiddle with it. Build it in clay.

The house served not only as a personal and family build but also as a space for Gene to display his interests and collections. The central corridor of the house was referred to as the “gallery,” housing two sets of Samurai armour, a vast book collection, many of which Gene bound himself, fly fishing gear highlighting his passion for Northwest recreations, and antique Japanese pottery. Scattered throughout the house were many Northwest Coastal Native American baskets, traditional Japanese chests, and farmhouse hooks called jizai-kagi, made of wood. Opposite the stone fireplace stood two totem poles carved by Duane Pasco, supporting large windows overlooking the vast wooded acreage of the Whidbey property.

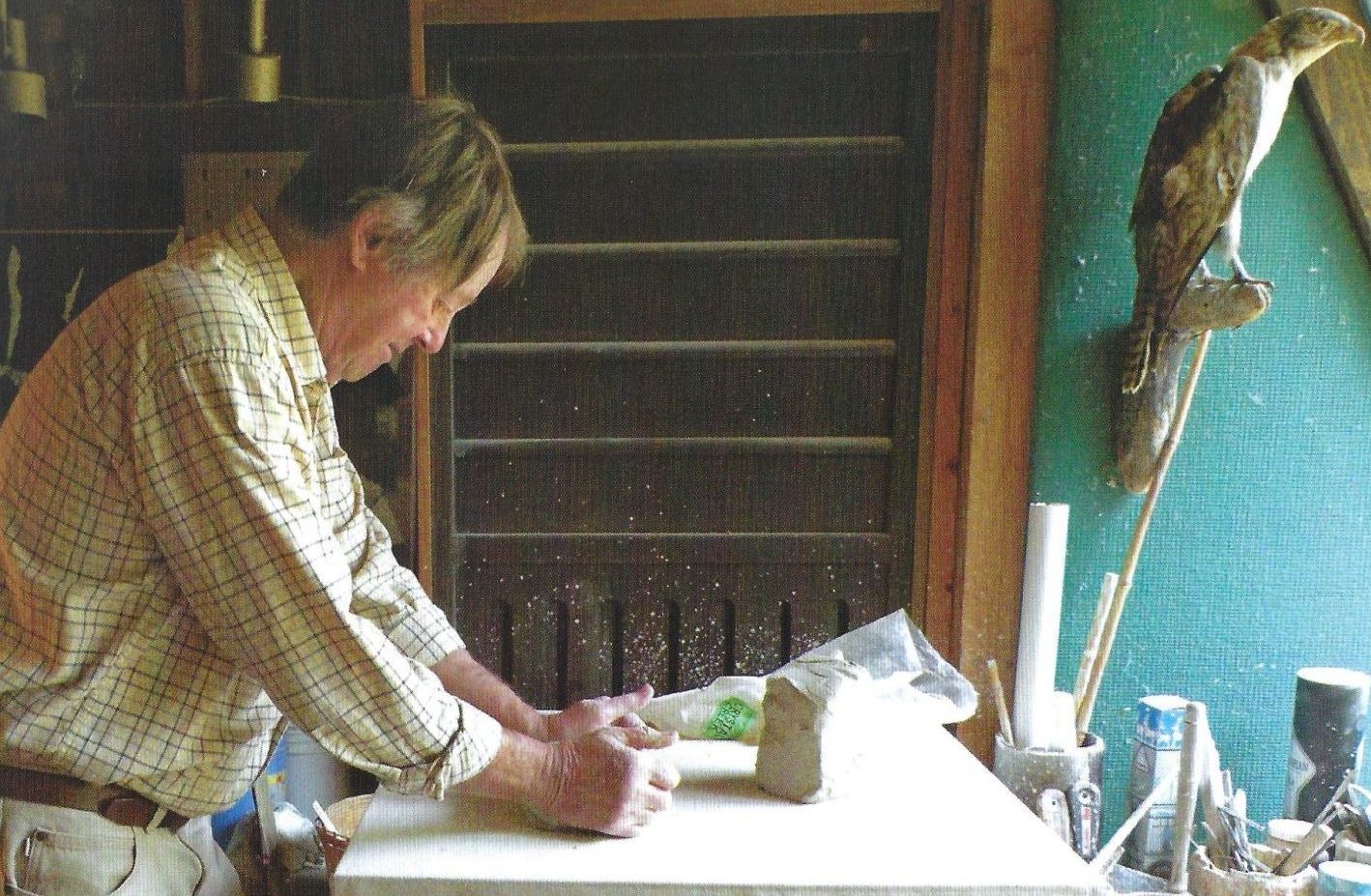

In 1993 Gene took up an interest in pottery. Again, the multi-talented artist embarked on creating and designing in a slightly different way. At the Whidbey property, he remodeled a workshop and built his own stone-fired kiln. Artists from around the area gathered to participate in the 3-day firings.

Gene’s legacy as a foundational part of the Northwest School style of design highlights his remarkable design capacity as an architect. But Gene’s involvement with all parts of his Pacific Northwest community, from his own collections to his work in preserving the natural beauty and ecology of the region and creating spaces with a local memory, makes him a truly unique artist.

Professor of Architecture, and designer of the CBE’s Gould Hall and the UW’s Moore Hall Annex, Gene Zema was committed to his craft and his passions. He contributed not only to the University but to the recognition of a Pacific Northwest style. He will be dearly missed by all.