Posted on April 30, 2025

Post categories: Alumni & Partners Architecture Honors & Awards News

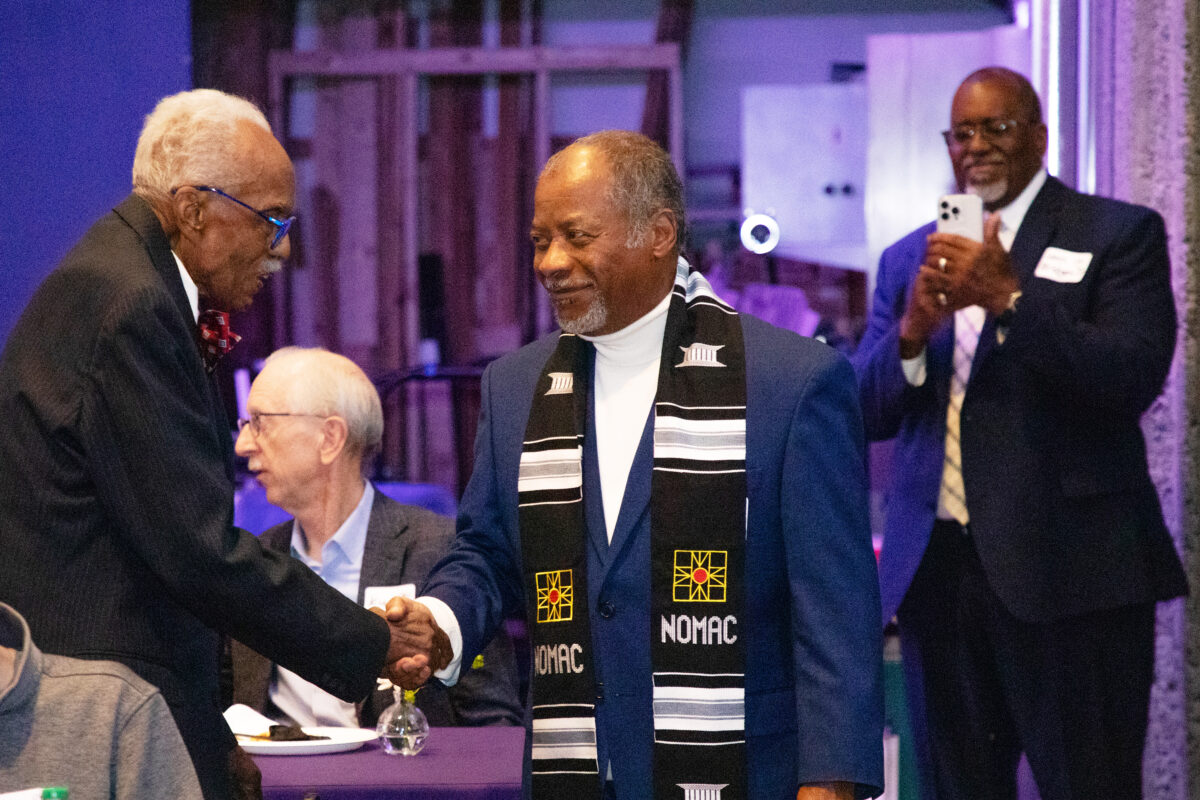

This spring, the Department of Architecture hosted the 2025 UW Architecture Alumni Awards, a bi-annual program that recognizes the significant contributions of alumni from the department’s undergraduate and graduate programs.

Among this year’s recipients was Leon Bridges, FAIA, a leading figure who founded Seattle’s second African American-owned architecture firm. Affiliate Professor Donald I. King, FAIA, had the honor of introducing Bridges, reflecting on the profound impact of mentorship across generations.

“All great mentors have great mentors,” King said. “Yours was famed African American architect and AIA gold medalist, Paul Revere Williams—the architect to the stars.”

Mentorship is not simply guidance. In architecture—where Black professionals represent less than 2% of licensed architects in Washington state, reflecting national disparities—mentorship is resilience, opportunity, and transformation. The careers of Leon Bridges, Donald King, and Rico Quirindongo show how mentorship can disrupt exclusion, cultivate leadership, and build a more inclusive profession.

Born in Los Angeles in 1932, Leon Bridges developed an early passion for architecture, often drawing house plans in his spare time. His ambitions, however, were not encouraged. As a teenager, a school counselor advised him against pursuing architecture because he was Black. Bridges’s course shifted when he met his mentor, a prominent Black architect and leader in the field, “My interest in architecture matured into a commitment after I met Mr. Paul Revere Williams, FAIA,” Bridges says.

Bridges’s path required perseverance. Drafted into military service during his studies at UCLA, he continued pursuing architecture while stationed in Japan. After earning his Bachelor of Architecture at the University of Washington in 1960, Bridges founded his own firm in Seattle before later becoming one of the first African American architects in Maryland.

Over his career, Bridges held leadership roles in the American Institute of Architects (AIA) and the National Organization of Minority Architects (NOMA). He received the 1998 AIA Whitney M. Young Jr. Award for his work advancing equity in the profession. After retiring from practice in 2005, he became an assistant professor at Morgan State University’s School of Architecture and Planning.

“Leon was one of those voices in my ear when others were telling me I couldn’t be an architect… He was the quintessential role model—someone you wanted to grow up to be like.”

Donald I. King, FAIA, Affiliate Professor, UW College of Built Environments

Mentorship was at the center of his mission, “I began to mentor around 1980, then began in earnest while I was teaching at Morgan State University, around 2000,” Bridges says. “My motivation was the terrifically low numbers of Black-owned architectural firms.”

For Bridges, mentorship was about more than career advice. It was about showing Black students and families that they belonged in a profession that had long excluded them and about building pathways where few had existed before.

Mentored by Leon Bridges, King has spent his career building on that legacy of pushing against systemic barriers and making space for others to thrive.

“Leon was one of those voices in my ear when others were telling me I couldn’t be an architect,” King says. “He showed me it was possible. He was the quintessential role model—someone you wanted to grow up to be like.”

King has more than 50 years of experience in architecture, urban design, and community planning, with a focus on housing, education, and healthcare. He is co-founder and Senior Director of Nehemiah Initiative Seattle and has held leadership roles across the profession. Since 2018, he has taught at the College of Built Environments at the UW.

From an early age, King was drawn to architecture, “By the age of 8, I saw a publication on the new town of Brasília and knew that I wanted to be an architect,” he recalls. “I was hooked and had no consciousness of the diversity issue as a challenge to my dream.”

At UCLA, King faced both encouragement and outright resistance, “It became evident that there were faculty who supported diversity, and those who opposed it,” he says.

In the face of that environment, King turned to mentorship, not just to uplift others, but to affirm his own place in a profession that often failed to see him, “Mentoring was one way of bolstering my own confidence and commitment to finish school,” he says. “And it laid the foundation for what would become a lifelong role.”

Throughout his career, King has prioritized presence and visibility, knowing firsthand the isolation that comes from being the only Black architect in the room.

“Many students from diverse backgrounds have never met an architect or seen one in their community,” he says. “I worked in the profession for two years before I met my first Black architect. It’s much harder to imagine yourself in a profession when you don’t see anyone who looks like you.”

King has also challenged the profession’s deep-rooted biases, advocating for practices that honor the lived experiences and cultural knowledge of the communities architects serve.

“I don’t need validation from those who think Europe is the source of all that is valid in design,” he says. “I’ve learned that an architect can engage with clients and communities in ways that honor their stories, not just the architect’s vision.”

“Donald laid the groundwork for me… What began as a mentor-mentee relationship eventually became a partnership.”

Rico Quirindongo, AIA, Director of the City of Seattle Office of Planning and Community Development

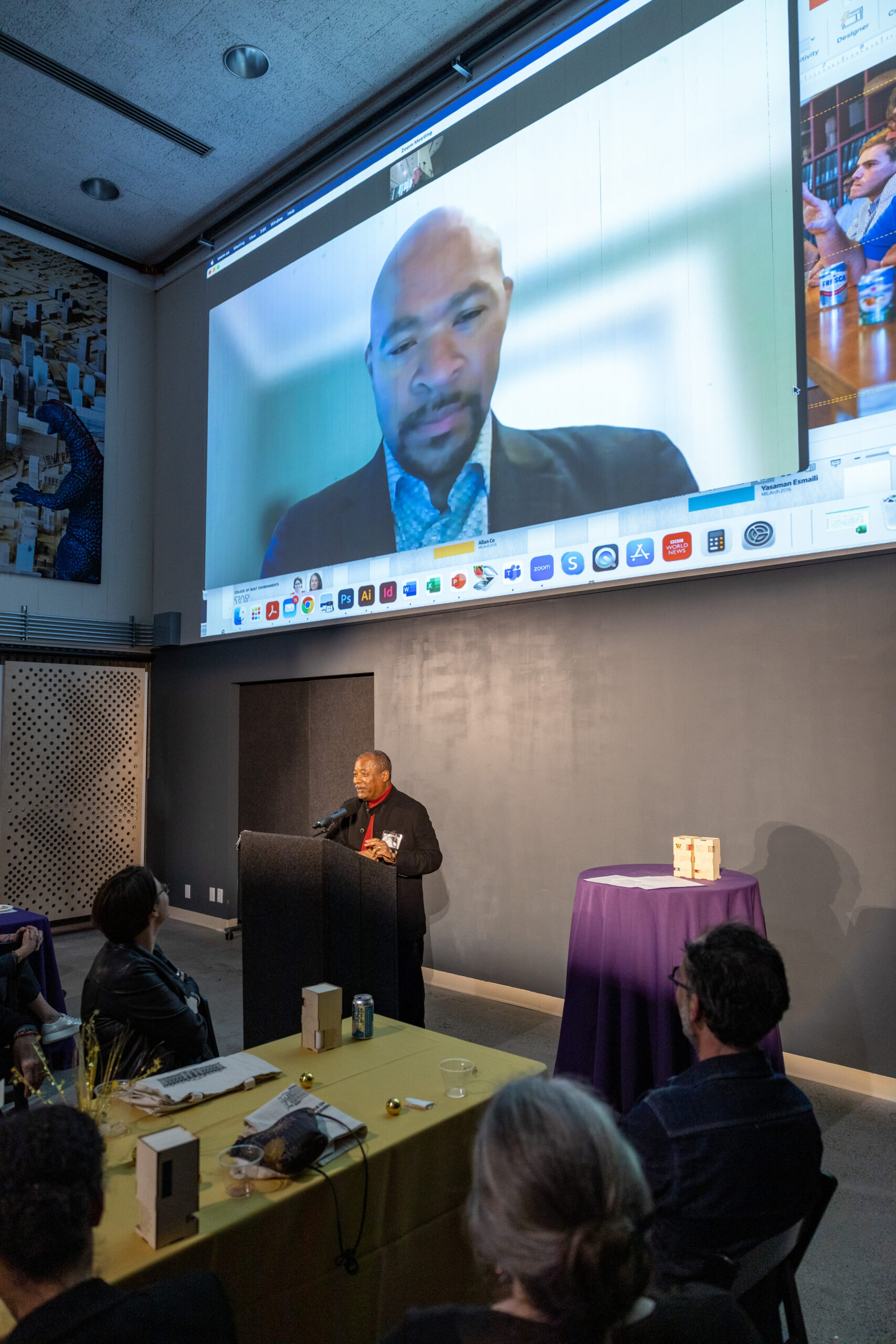

King’s mentorship helped open the door for city leaders like Rico Quirindongo, AIA, Director of the City of Seattle Office of Planning and Community Development. Early in Quirindongo’s career, King entrusted him with a major civic project—an opportunity that would shape his future. Like the relationship between Bridges and King, their connection reflects a powerful legacy: not just surviving in a profession not built for them, but changing it for those who would come next.

Quirindongo, a graduate of UW’s Master of Architecture program, represents the next generation shaped by that legacy. Over the past 30 years, he has worked to revitalize historic neighborhoods, landmarks, and public spaces through civic design and community engagement. A founding member of NOMA NW and a former AIA Seattle president, Quirindongo has led efforts to center equity in the built environment. His leadership has been recognized nationally, including his designation as a Citizen Architect by AIA National and multiple distinguished alumni awards from UW.

As a child, Quirindongo built forts and imagined new worlds, drawing inspiration from science fiction, figures like Harriet Tubman, and stories of liberation. In high school, he realized architecture could combine art, math, and justice, and that realization fueled his path forward.

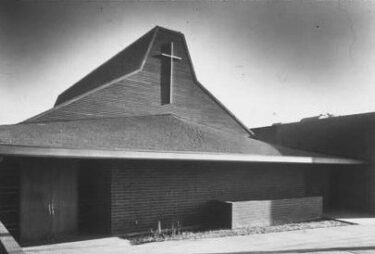

While at UW, Quirindongo joined an initiative to create an African American museum in Seattle’s Central District. He wrote a $300,000 grant to launch the design effort and became the project architect, working under the guidance of Donald King.

“Donald laid the groundwork for me,” Quirindongo says. “He gave me opportunity, trust, and guidance. What began as a mentor-mentee relationship eventually became a partnership.”

Raised in a predominantly white suburb, Quirindongo learned early how to navigate spaces where he was often the only person of color, “I learned how to lead, how to show up, how to speak up,” he says.

That experience drives his commitment to ensuring that future generations of students of color find not only access to the profession but also belonging and leadership.

“I needed that mentorship,” he says. “I’m here because of generations of Black and white people who sacrificed and uplifted others. I owe it to my community to do the same.”

Today, Quirindongo supports students through NOMAS UW, the UW chapter of the National Organization of Minority Architecture Students. The student-led group plays a vital role in shaping the experience of students from underrepresented backgrounds, offering site visits, networking events, design competitions, and a powerful sense of community.

Mentorship is at the heart of NOMAS. The organization brings in outside professionals—especially architects of color—to offer guidance that goes beyond technical skills, helping students envision new pathways into leadership and design.

“Don’t wait for a future you’re not building… We’re here to help, but you’ve got to pick up the baton.”

Rico Quirindongo, AIA, Director of the City of Seattle Office of Planning and Community Development

Despite a demanding schedule, Quirindongo remains an active mentor, professor, design reviewer, and advocate. Students describe him as thoughtful, rigorous, and inspiring.

“He brings charisma and charm to his insights and encourages students to work for more than themselves and their worldviews,” says Davien Graham, president of NOMAS UW. “Personally speaking, he’s the best reviewer I’ve ever had because of his criticality, humor, and desire to see students grow beyond their limits.”

The legacy of mentorship also extends through NOMA NW, which continues to support NOMAS UW with funding, advising, and professional development, ensuring a strong, intergenerational network for future architects of color.

Through their work as architects, educators, and mentors, Leon Bridges, Donald King, and Rico Quirindongo have helped shape not only the built environment but the pathways into it. Their stories demonstrate that representation is about more than access but about creating the conditions for students and emerging professionals to thrive, lead, and uplift others.

As Quirindongo reminds emerging professionals: “I tell students—don’t wait for a future you’re not building. You don’t need permission to show up and use your voice. We’re here to help, but you’ve got to pick up the baton.”

Learn more about mentorship opportunities at the College of Built Environments.